Why is everyone talking about Iceberg?

About a year ago, I left my job as a machine learning engineer to start my company. My day to day moved away from data infrastructure to running a business. As I jump back into it, I see a few important transitions have happened.

Everyone I talk to says Iceberg at least once in the conversation.

If you are in the same boat trying to understand the hype about Iceberg in the data community or decide what storage you want to use for your data platform, this post is for you. This post is a dive—into why Iceberg matters, how it stacks up against Delta Lake and Hudi, and what a real-world example of analyzing YouTube videos looks like with Iceberg.

Lakehouses are taking center stage for data platforms and open table formats are making it happen. Data lakehouses have been evolving from messy storage of random files in blob storage to a true source of insights and data workloads for teams.

Back in 2015 a "data lake" meant Hive folders on HDFS:

- On‑prem HDFS + Hive dirs. Storage and metadata lived on a single cluster and disks were your capacity ceiling.

- Zero ACID & brittle schema. Adding a column meant drop + recreate—and pray downstream jobs didn't explode.

- Ops‑heavy partition fixes. Two engineers were on-call every time marketing asked for yesterday's numbers.

Fast‑forward to 2025:

- Cheap cloud object stores. S3 / GCS / ABFS decouples storage from compute and scales elastically.

- Open table formats add ACID. Iceberg / Delta / Hudi layer transactions + schema evolution straight on Parquet.

- Multi‑engine, self‑serve SQL. Spark, Flink, Trino, DuckDB, Snowflake all query the same tables—no

msck repair, no weekend fire‑drills.

My take: You're not just picking file layouts anymore—you're choosing the single source of truth your whole data stack will trust. The ultimate goal here is to build a data lake that can be queried from all the different compute engines (Spark, Snowflake, Flink, Trino, DuckDB, etc.)

So what is this Iceberg?

Imagine! What if your S3 data lake behaved like a warehouse—without locking you into one vendor?

That's the core promise of Apache Iceberg. Born at Netflix, nurtured by Apple, AWS & LinkedIn, Iceberg turns humble Parquet files into fully transactional tables you can query from Spark, Trino, Flink, or even DuckDB on your laptop.

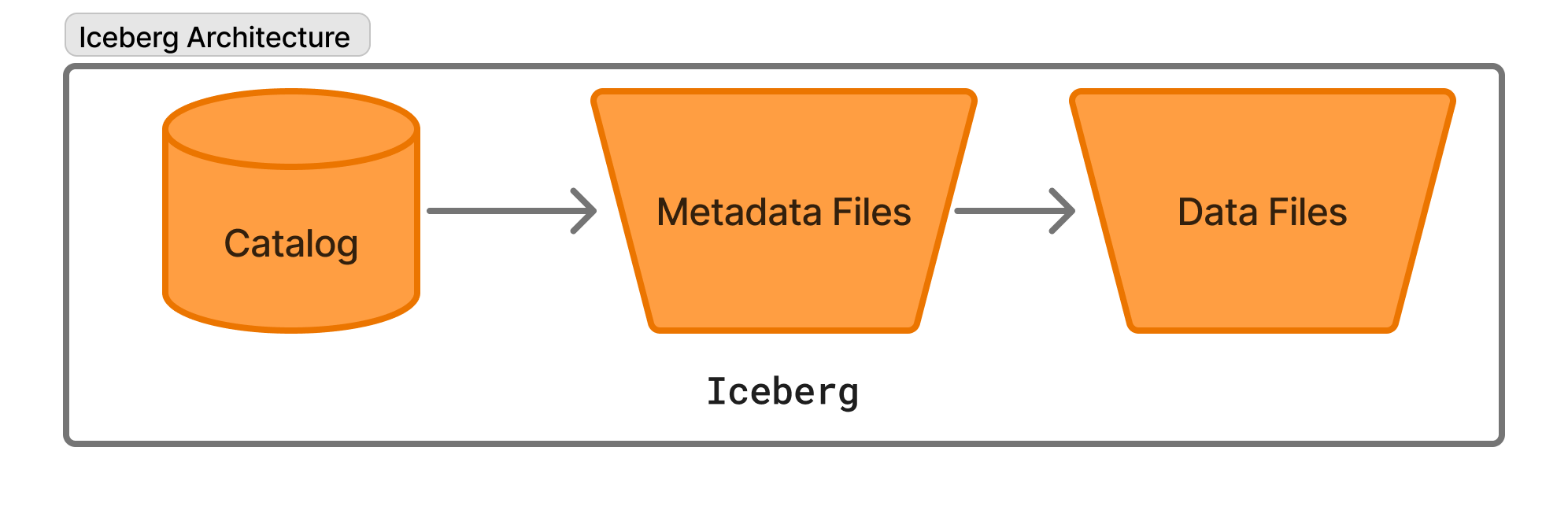

Iceberg's architecture is three simple layers:

- Data files – immutable Parquet/ORC on S3.

- Metadata & manifests – tiny Avro/JSON files listing data-file stats.

- Catalog – pointer to the current snapshot.

Together, they unlock features you used to pay a warehouse for.

Every write is a snapshot, we get ACID by metadata swaps

New data files and a brand-new snapshot are created for every new write. Metadata keeps track of which snapshot to choose. So there is a point-in-time consistent view of the data.

Source: Incremental Processing using Netflix Maestro and Apache Iceberg

In the GIF above you can see how different snapshots are created for the writes coming in.

There are two main ways you can do row-level changes (CRUD):

- Copy-on-Write (COW): When you run an UPDATE, DELETE, or MERGE, Iceberg rewrites the affected data files. This means your table always reflects the latest state in-place, and queries don’t need to merge data at read time. It’s simple and great for batch workloads, but can be more I/O intensive for frequent updates.

- Merge-on-Read (MOR): Here, updates and deletes are written as new “delta” files, and the actual merging happens when you read the data. This is more efficient for high-velocity, streaming, or CDC workloads, since you avoid rewriting big files on every change. The tradeoff: reads have to do a bit more work to stitch together the latest view.

My takeaway: No global locks; writers only fail when they touch the same rows. Spark, Flink, and Trino all leverage this commit model out of the box.

Iceberg will hide your partitions and evolve your schema without data rewrites

I used to spend weekends manually reorganizing Hive partitions—renaming folders, running msck repair, hoping queries wouldn't break. With Iceberg, partitions live in metadata, not directory names.

Here's what that unlocks:

-

Define once, adapt forever. You create the table with an initial spec:

CREATE TABLE watch_events ( user_id BIGINT, event_ts TIMESTAMP, action STRING ) PARTITIONED BY (days(event_ts));When your analytics team later asks to segment by

region, you simply:ALTER TABLE watch_events ADD PARTITION FIELD region;No file rewrites, no directory shuffles—Iceberg's manifest tracks both old and new layouts.

-

Real-world change is messy—partitions shift constantly. Content launches in new countries, user cohorts evolve, data schemas expand. You can now easily add or modify partition fields dozens of times without downtime or backfills. Iceberg handles the mix of old and new partitions transparently.

-

Query pruning stays razor-sharp. Even if your SQL omits

region, the engine still consults the metadata to skip irrelevant files, just like it would forevent_ts. That means performance doesn't regress as your partition strategy evolves.

Why it matters: Experienced engineers know that partition churn is inevitable. Hidden, metadata-driven partitions with Iceberg's dynamic spec mean you can iterate on your data model, without painful rebuilds or weekend firefights.

Point-in-Time queries made easy with time-travel snapshots

I used to spend days to figure out simple what-if analyses before. What if we ran our model on the data before we changed the definition of this feature?

Another problem was debugging ETLs. Here is how I can debug and rerun my ETL by replicating the input data for it in 1 line.

SELECT *

FROM prod.streaming.watch_events

FOR TIMESTAMP AS OF '2025-05-05 00:00:00';Iceberg does this by using multi-level metadata hierarchy. It has a root metadata file, manifest list, manifest files themselves and finally the data files.

Another useful benefit of this is snapshots + retention policies = built-in audit and GDPR compliance (expire_snapshots after 90 days).

Are there any nuances or does Iceberg rule them all?

When I first needed petabyte-scale batch reads and multi-engine support (Spark jobs, Trino queries and ad-hoc DuckDB analytics), Iceberg's manifest-tree metadata won me over.

But, that's not the whole picture, here is how I look at it.

- High-velocity CDC & real-time merges? At one client ingesting 10k CDC events/sec, Apache Hudi's native upsert streams (Merge-On-Read + timeline) handled corrections without custom polling.

- All-in on Databricks? Early in my career, Delta Lake's transaction log and built-in Change Data Feed on Databricks simplified merges and streaming pulls.

- Open, multi-engine needs? When pipelines spanned Spark, Athena, and DuckDB, only Iceberg was supported without bespoke connectors.

| Workload pattern | Why it matters | Format to use |

|---|---|---|

| Petabyte append-only | Consistent snapshots, hidden partitions | Iceberg |

| Micro-batch CDC & merges | Real-time upserts + change feeds | Hudi / Delta |

| Databricks-native | Integrated with DBFS & Unity Catalog | Delta Lake |

My take: No single format rules them all—match tool to task. For most streaming analytics, Iceberg's openness and agile partitions win. But for ultra-low-latency CDC or tight Databricks integration, Hudi or Delta still shine.

If you made it this far, its only fair I show you an example implementation to ground your theoretical understanding of Iceberg.

How would you build a YouTube channel analytics system with Iceberg + DuckDB?

Let's retrieve YouTube engagement data for your channel

We'll pull daily snapshots of every video on a channel using the YouTube Data API v3. In production you'd run this as a daily job; here's the core logic:

import os, datetime

from googleapiclient.discovery import build

API_KEY = os.getenv("YOUTUBE_API_KEY")

CHANNEL_ID = "UC_x5XG1OV2P6uZZ5FSM9Ttw"

SNAPSHOT_DATE = datetime.date.today()

youtube = build("youtube", "v3", developerKey=API_KEY)

# ── 1) Fetch all uploads playlist for channel

pl_resp = youtube.channels().list(

part="contentDetails", id=CHANNEL_ID

).execute()

uploads_pl = pl_resp["items"][0]["contentDetails"]["relatedPlaylists"]["uploads"]

# ── 2) Iterate through playlistItems to collect video IDs

video_ids = []

next_page = None

while True:

pi = youtube.playlistItems().list(

part="contentDetails",

playlistId=uploads_pl,

maxResults=50,

pageToken=next_page

).execute()

video_ids += [item["contentDetails"]["videoId"] for item in pi["items"]]

next_page = pi.get("nextPageToken")

if not next_page:

break

# ── 3) Batch stats calls (100 IDs per request)

records = []

for i in range(0, len(video_ids), 50):

batch = video_ids[i:i+50]

resp = youtube.videos().list(

part="snippet,statistics",

id=",".join(batch)

).execute()

for item in resp["items"]:

stats = item["statistics"]

records.append({

"video_id": item["id"],

"title": item["snippet"]["title"],

"channel": item["snippet"]["channelTitle"],

"date": SNAPSHOT_DATE,

"views": int(stats.get("viewCount", 0)),

"likes": int(stats.get("likeCount", 0)),

"comments": int(stats.get("commentCount", 0))

})

# `records` is now a list of daily metrics for every video on the channel

We should define the data model & Iceberg tables

We'll separate video_info (static) from video_metrics (time-series), and add a hidden partition on date and a 16-way hash bucket on video_id to optimize parallel reads:

from pyiceberg.schema import Schema

from pyiceberg.types import NestedField, StringType, DateType, IntegerType

from pyiceberg.partitioning import PartitionSpec

# ── Schemas ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

video_info_schema = Schema(

NestedField(1, "video_id", StringType(), required=True),

NestedField(2, "title", StringType(), required=True),

NestedField(3, "channel", StringType(), required=True)

)

video_metrics_schema = Schema(

NestedField(1, "video_id", StringType(), required=True),

NestedField(2, "date", DateType(), required=True),

NestedField(3, "views", IntegerType(),required=False),

NestedField(4, "likes", IntegerType(),required=False),

NestedField(5, "comments", IntegerType(),required=False)

)

# ── Partition Spec ────────────────────────────────────────────────────

metrics_part_spec = (

PartitionSpec.builder_for(video_metrics_schema)

.identity("date")

.bucket("video_id", 16)

.build()

)

Setup your local Iceberg data store

We'll use a SQLite catalog and local filesystem warehouse:

# .pyiceberg.yaml in your project root

catalog:

local:

uri: sqlite:///iceberg_catalog/catalog.db

warehouse: file://$(pwd)/iceberg_catalog

import os

from pyiceberg.catalog import load_catalog

os.environ["PYICEBERG_HOME"] = os.getcwd() # ensure .pyiceberg.yaml is picked up

catalog = load_catalog("local")

# Create namespace & tables if not exist

catalog.create_namespace_if_not_exists("youtube")

catalog.create_table_if_not_exists(

("youtube", "video_info"),

schema=video_info_schema

)

catalog.create_table_if_not_exists(

("youtube", "video_metrics"),

schema=video_metrics_schema,

partition_spec=metrics_part_spec

)

On disk you'll see:

iceberg_catalog/

└── youtube/

├── video_info/

│ └── metadata/

└── video_metrics/

└── metadata/

Ingest data into Iceberg tables

Append both dimension and fact data in PyArrow batches—Iceberg will atomically produce new snapshots:

import pyarrow as pa

# Load tables

info_tbl = catalog.load_table(("youtube","video_info"))

metrics_tbl = catalog.load_table(("youtube","video_metrics"))

# Upsert static video_info (overwrite or merge as needed)

info_arrow = pa.Table.from_pylist(

[{**r, "title":r["title"], "channel":r["channel"]} for r in records],

schema=info_tbl.schema().as_arrow()

)

info_tbl.replace_partitions(info_arrow) # idempotent replace of dimension data

# Append the new snapshot of metrics

metrics_arrow = pa.Table.from_pylist(records, schema=metrics_tbl.schema().as_arrow())

metrics_tbl.append(metrics_arrow)

This write:

- Creates Parquet files under

video_metrics/data/... - Updates Iceberg's manifest JSON to include only the new files

- Guarantees ACID isolation if multiple writers run concurrently

Finally, ask some useful questions about our videos

We can push down Iceberg metadata pruning into DuckDB via PyIceberg's scan().to_arrow(), then run high-level analytics:

import duckdb

conn = duckdb.connect()

# register as Arrow tables

conn.register("video_info", info_tbl.scan().to_arrow())

conn.register("video_metrics", metrics_tbl.scan().to_arrow())

# Example: top 5 videos by daily delta views

print(conn.execute(

"""

SELECT

m.video_id, i.title,

m.date,

m.views - LAG(m.views) OVER (

PARTITION BY m.video_id ORDER BY m.date

) AS delta_views

FROM video_metrics m

JOIN video_info i ON m.video_id = i.video_id

WHERE delta_views IS NOT NULL

ORDER BY delta_views DESC

LIMIT 5;

"""

).fetchall())

Here you see:

- Manifest pruning: DuckDB only reads files with

datefilter. - Hash-bucket partition: parallelizes scan across 16 buckets.

- Window functions: easily compute trends.

There you have it—now you can ask your LLM to design queries to answer all the questions your heart desires for your YouTube channel.

Iceberg vs. The Rest: Performance & Cost Showdown

What are the performance numbers to compare the table formats? At scale that is a big factor to adopt something new like Iceberg.

| Workload (1 TB TPC-DS, 8 vCPU) | Iceberg | Delta | Hudi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure scans (Q3, Q96) | 1 × baseline | 1.1 × | 1.2 × |

| Merge-heavy (Q18) | 1.4 × | 1 × baseline | 1.1 × |

| Incremental read | 1 batch / min | Change Feed @ 10 s | Hudi MOR @ 3 s |

Cost angles:

- Snapshot & manifest files add ~0.5 % storage overhead—cheap.

- Biggest spend is still read I/O; schedule weekly

rewrite_data_files+compactto keep file sizes sweet-spot (256 MB). - Resist the urge to bucket by every dimension—Iceberg stats already prune aggressively.

My Takeaway: Iceberg is fastest for large, append-only analytics; Delta/Hudi gain edge once your workload hammers a lot of updates.

Iceberg delivers warehouse-class reliability, schema flexibility, and time travel—without shackling you to a closed ecosystem. It also has the highest levels of support in the data platform ecosystem. Iceberg actually just makes the lakehouse promise a reality. Lakehouse architectures will finally be stable enough to trust in production. That's exciting!